Nearly 100 years after Sir Alexander Fleming kicked off the antibiotic age with his accidental discovery of penicillin, a Viterbo University professor and select students are conducting research they hope will lead to another life-saving discovery.

Some students in Viterbo’s Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) program have been conducting research aimed at discovering new antibiotics that will defeat life-threatening infections caused by increasingly prevalent antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The answer could be right under our feet. Specifically, in the dirt.

“In one teaspoon of soil, you’ll find a billion bacteria and 10s of thousands of species,” said Luke Bussiere, a Viterbo biology faculty member since 2021. “Researchers have been looking for antibiotic producers in the soil for a long time. Probably a majority of the antibiotics that anybody has been given for an infection came from some bacteria that was growing in the soil.”

“There’s a lot of competition between those bacteria,” added student researcher Emma Schoen, “and one way they can preserve their space and nutrients is to produce antibiotics that inhibit the growth of other bacteria.”

The trick is to find antibiotic-producing bacteria that haven’t been found before. “If resistant microbes haven’t seen this new antibiotic before, there’s a good chance they won’t have resistance and we could use it to wipe out these infections that are plaguing people,” Bussiere said. “If we did find a new bacteria, it could lead to a new antibiotic used in a clinical setting.”

“And I would get to name it,” Schoen added with a laugh.

Schoen is a biochemistry major (with a Spanish minor) starting her junior year and working toward a career as a physician assistant. She worked with soil samples from six sites, including a spot rich with horse manure (and, it turned out, antibiotic-producing bacteria) from her home near Richland Center.

“My main goals for my SURF experience coming in were learning more communication skills with professionals and then bettering my skills in the lab and research skills in general,” Schoen said.

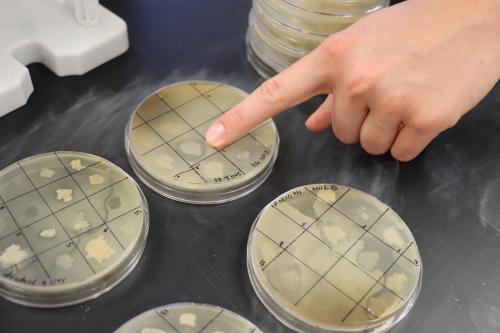

In the course of eight weeks, Schoen took her dirt samples and cultivated isolated bacterial colonies, looking for evidence of antibiotic production. What she was looking for is a blank space around the colony where the underlying test bacteria base could not grow. It’s known as a “zone of inhibition.”

Schoen, a hurdler on the Viterbo track team, found two promising examples of strong antibiotic producers. She prepared them for genetic sequencing by amplifying the DNA through polymerase chain reaction. The samples will be analyzed by a company that specializes in genetic testing.

A fellow track team member, Gabe Holderby, also worked with Bussiere on antibiotic research this summer, but his work had a different twist. A biology major minoring in business administration and ethics, Holderby plans to go to dental school and establish his own orthodontics practice.

Instead of analyzing soil samples, Holderby wanted to seek antibiotic producing bacteria that live in the human mouth. Rather than go directly into people’s mouths, though, he found another vehicle to get samples: discarded chewing gum.

“I wanted to do some research that would make me stand out as a dental school applicant,” said Holderby, who qualified for the national track and field championship event in the javelin throw.

Before Bussiere approved Holderby’s research proposal, he did some research himself. “It wasn’t completely clear to me that gum would have antibiotic producers, but what I did find is there seem to be some people who naturally don’t get cavities and one of the thoughts is it might be due to bacteria in the mouth that might be inhibiting bacteria,” Bussiere said.

Holderby’s research found three bacterial samples that showed promise as antibiotic producers, including one variety that created a zone of inhibition with a test base of Streptococcus mutans, a strain of bacteria known to cause tooth decay.

Any given summer, Viterbo will have a dozen or more students working on SURF projects on a wide range of topics. Student participants get paid for their work and can choose to do their research part time or full time.

For students with science-related majors, the SURF experience gives them a jump on their required three-semester research class sequence, allowing them to get more in depth with their work.

Having SURF students also helps professors advance their related major research projects. Bussiere started his search for new antibiotics last year after his previous work related to viral cancer treatments.

Bussiere knows it’s a long shot that he’s going to turn up a species of antibiotic-producing bacteria that’s never been seen, but it’s certainly not impossible.

“I always like to have a lofty goal behind my research, realizing that we will likely have a small impact. If you don’t set a lofty goal, you’ll definitely never reach it,” Bussiere said. “The goal here would be to get an antibiotic into the clinical setting someday to help target drug-resistant microbes.”