Since graduating from Viterbo with a biology degree in 1978, Joe Paulauskis, a self-described “kid from a dairy farm,” has led a remarkably impactful life of science, as a researcher, teacher, and innovative leader in both industry and academia.

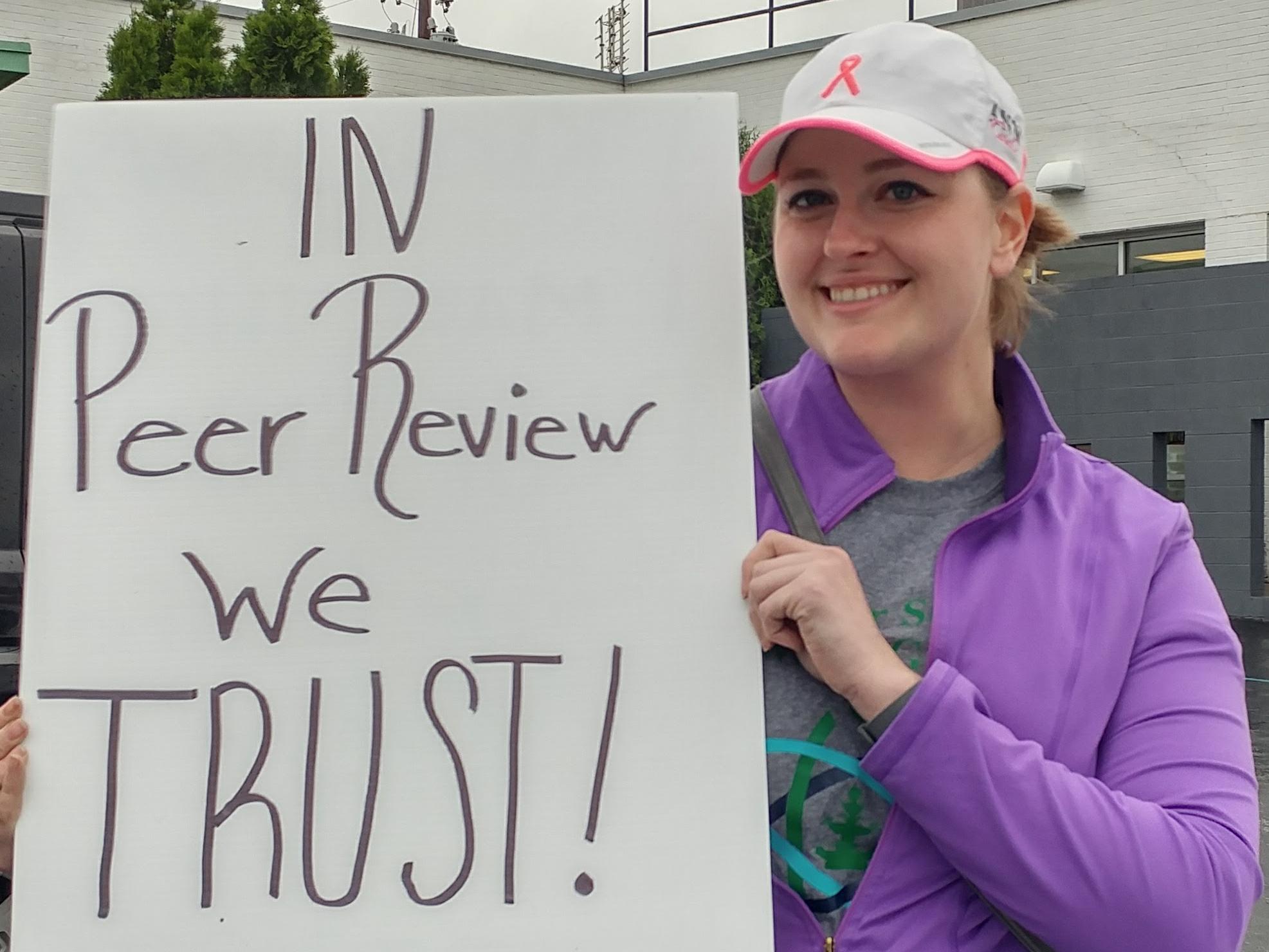

Paulauskis has been at the forefront of efforts to harness the power of genetic sequencing to ensure that patients get medications that will help them the most (and harm them the least). Paulauskis also played a major part in streamlining the overseas approval process for U.S. made pharmaceuticals, and he was a leading player in establishing a tissue bank system that saves time and money for cancer researchers.

For 16 years, Paulauskis taught and did research at Harvard University, 11 of those years as a professor of molecular biology. After leaving Harvard he was tapped as global head of pharmacogenomics for pharmaceutical giant Pfizer, helped the National Institutes of Health construct the world’s most comprehensive cancer tissue biobank (The Cancer Genome Atlas), and served as chief operating officer for Paradigm, a groundbreaking company that used next-generation DNA sequencing of tumors to ensure cancer patients were getting the drugs that would work best for them.

Then his career path turned back to academia and laboratory science, taking him to the University of Michigan, where he had earlier taught as an adjunct pathology professor and established and run the Genomic Pathology Laboratory and Molecular Toxicology and Pharmacogenomics Laboratories for Pfizer. Paulauskis recently retired as associate director of the University of Michigan Medical School’s Central Biorepository.

Reflecting on his life of science and innovation (which is far more expansive and impressive than the preceding summary indicates), Paulauskis said perhaps his most important contribution to society has been training and mentoring countless researchers contributing to progress in the fight against disease and the human suffering it causes.

Paulauskis knows well the difference a great teacher and mentor can make. His own life and career path would have been a lot different, if not for a creative nudge from an influential Viterbo professor.

The path to Viterbo

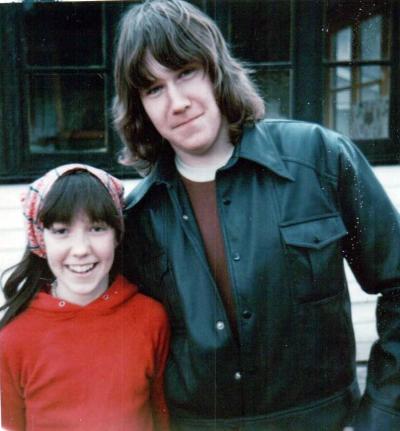

The eldest of five children in his family (and the only son), Paulauskis spent the first part of his childhood in the Chicago area. But after his parents divorced and his mother remarried, the family moved to a dairy farm near Viola. He was 13 when they moved to Wisconsin.

All the children took on the last name of their stepfather, Gauss, and that’s how Paulauskis was known until his stepfather died and he reverted to his surname at birth.

Neither of his parents had college degrees, and Paulauskis didn’t really have an idea of how to pick a school or what higher education would involve. But he knew about Viterbo because of its sponsorship of the high school quiz show that he would watch on television. The quiz bowl team from his school, Kickapoo High School, won during its appearance on the show, procuring a scholarship for somebody at the school to attend Viterbo.

“I was never a great student, but I always felt like biology and chemistry were easy for me, and physics and math, too,” Paulauskis said. “I figured I’ll either go to Harvard or Viterbo.”

He applied to Harvard but withdrew his application, deciding to go to Viterbo after a campus visit during which he met with a biology professor and department chair, Joe Kawatski. “He promised me I could start doing research on day one,” recalled Paulauskis. That had a strong appeal.

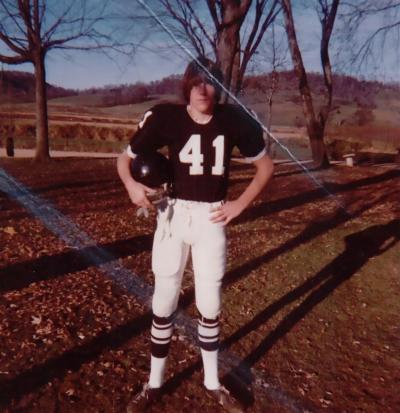

When Paulauskis came to Viterbo in 1974, it had only been co-ed for a few years. The male students living on campus were in houses, which took on the names of their first resident advisors. Paulauskis, who later became an RA himself, first lived in “Schoonover House,” named for Dave Schoonover '76 , with whom Paulauskis formed a tight friendship.

Early in his first year, Paulauskis recalled all the male students meeting as a group with the president. There were nine female students for every male student, the president said, admonishing the men to be on their best behavior. At that point, Paulauskis recalled, someone in the back of the room said loud enough for others to hear, “Are the girls assigned to us or do we get to choose them ourselves.”

Diving into science

True to his word, Kawatski gave Paulauskis the chance to get involved in research right away. Kawatski’s research focused on aquatic toxicology, in particular trying to ascertain whether pesticides used to control the sea lamprey population in the Great Lakes also killed other creatures. Paulauskis and other students were awarded paid positions in the summer to perform research.

“You couldn’t not fall in love with limnology and toxicology working with him,” Paulauskis said of Kawatski. “He could make it so fascinating.”

The first of many, many research papers that Paulauskis has had published was co-authored with Kawatski and Dr. Carl Hansen ’76. The paper detailed the results of research to see if the kidney-like structures of aquatic midge larvae could process a pesticide. Paulauskis had to remove the tiny kidneys from midges and keep the organs alive long enough to bathe them in radio-labeled pesticide and to determine if there was movement of the pesticide through the kidney.

Thousands of small scintillation vials were used in the research, and halfway through Paulauskis’s senior year Kawatski gave him the painstaking task of cleaning them. By the time he got done, Paulauskis was feeling aggravated and aggrieved, and he asked Kawatski why he had made him clean all those vials.

“He said, ‘You should get used to it. If you’re going to be a lab technician you have to do that kind of thing,’” Paulauskis recalled.

The vial cleaning, Paulauskis discovered, was Kawatski’s way of getting him to rethink his decision not to go to grad school, and it worked. With Kawatski’s help, Paulauskis won admission to multiple graduate school programs, settling on Miami University in Ohio. He tied his mattress to the roof of his 1968 Mustang and headed east.

Onward and upward

Seven years (and a lot of aquatic toxicology research) later, Paulaskis had earned master’s and doctoral degrees in zoology, and he was ready to follow in the footsteps of Professor Kawatski. After a couple interviews at colleges, though, he discovered he would likely be so loaded down with teaching duties that he wouldn’t have time to do the research that he loved.

With his innate curiosity, that wasn’t the life for him, so he set his sights on becoming an expert in an emerging field: molecular biology. “This field of study was brand new and hot, very exciting,” Paulauskis said. “It was quite a jump for me.”

Think midge larvae kidneys are small? Paulauskis would soon be working at the subcellular level, snipping and cloning fragments of DNA, the genetic material at the heart of all living things. As a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University for five years, Paulauskis delved into how inhaled metal particles effect the lungs, how the immune system knows the particles are there, and why immune systems sometimes mount an overzealous response to the particles that is more hazardous to a person’s health than the metal itself would be.

“I think I pushed the field forward with everybody else at Harvard. I helped do a few things,” Paulauskis said, perhaps with a bit too much Midwestern modesty.

After his postdoctoral work was complete, Paulauskis stayed on at Harvard for 11 more years as a professor of molecular biology. “Harvard is such a great place to work. It’s a lot of fun,” Paulauskis said. “Leaving Harvard is a hard thing to do. It’s a great place, but it’s actually an even better place to be from.”

While at Harvard, he was asked to come to Pfizer’s facility in Connecticut to give a tutorial on molecular biology, and his presentation made an impression on some influential people at the company. “They said, ‘Why are you playing around in academia? Come to Pfizer, and we’ll give you an unlimited budget to build a pharmacogenomics lab,’” Paulauskis said.

Pfizer’s offer was impossible to resist, and Paulauskis was thrust into the first of many leadership roles he held in both industry and academia over the past 20 years.

He made the wrenching decision to retire earlier this year and move from Ann Arbor, Mich., to coastal Massachusetts because he needed time and space to deal with health issues. He’s feeling great these days and looking for a house with his wife, Lisa, a Boston native he met while he was at Harvard.

Moving back to the East Coast was a big attraction for them, too, because it would bring them closer to their daughter, Carly, who works in fashion in New York City (she has held several roles with shoe design companies, including one started by Sarah Jessica Parker).

Paulauskis still has the urge to teach and mentor budding researchers, and one path forward he is contemplating is to find a house near a small college like Viterbo where he could get back in the classroom. “Doing something like that would be poetic somehow, like coming full circle,” he said.